Cover photo: a US citizen would have to buy 109 bottles of Air Vodka ©️ carbon negative vodka to offset their carbon footprint for one day. Copyright: Science Museum

“Drought, food insecurity and flooding are already forcing people to move,” states the voiceover to a cartoon of faceless people pulling suitcases towards coaches. “By 2050 over a billion people could face displacement.”

The animation cuts to a sea of pixelated stars as a message fills the centre of the screen; “This doesn’t have to be our future.”

‘Our Future Planet’ is an ambitious – even grandiose – title for a small exhibition. Reading any Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report covering climate tipping points will show that it is not easy to map out the future. It is even more difficult to imagine a future without drought, food insecurity or flooding.

So what does this utopian future look like? According to the UK’s Science Museum, and by implication Shell, the oil and gas giant sponsoring the exhibition, it looks like a corporate expo. Experimental products on display include carbon-negative yoga mats and toothpaste, and a huge Climeworks logo looms behind TV screens of executives lobbying for funding.

Parked in the back corner of the building by the café and toilets, this free-to-enter maze of branding is filled with optimistic platitudes. “No technology or person can stop climate change alone. But together, there is hope” is written on the wall as you enter.

Drax to the future: burn trees, replace them with robots

After a small section on tree planting (good for biodiversity, air quality, and climate, but “tricky” because it “competes” with “economic benefits”), we are straight onto Drax. Drax Power are a bioenergy company who run the tree-burning power plant that is the UK’s largest single source of CO2 emissions.

The company is currently facing several legal challenges. One concerns allegations from the Health and Safety Executive that they have endangered workers through exposure to wood pellet dust and “hazardous substances”. Another involves the OECD reviewing allegations that Drax have made “various misleading or inaccurate statements” about the carbon neutrality of their business.

That is not all. UK Parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee recently concluded an active inquiry into the sustainability of biomass imports after BBC Panorama accused Drax of burning primary forest. They are facing major accusations of environmental racism in the USA, and Sir David Attenborough recently criticised tree-burning in The Daily Mail.

In other words, Drax are in desperate need of some good PR, and their fingerprints are all over this exhibition. Not just in the literal video advert where their Head of Bioenergy, Carbon Capture and Storage touts proposals for adding carbon capture and storage technology to their Yorkshire powerplant, or in the exhibits they have contributed to directly, but in the other collaborators in this exhibition too.

A bottle of solvent is donated by C-Capture, a company in part owned by Drax. Information labels cite White Rose reports produced by Capture Power Limited (CPL), an industrial consortium formed by General Electric, BOC and Drax. Even the few academics given space alongside companies have Drax ties – such as Yadvinder Malhi, an Oxford professor who oversaw a literature review for Drax’s Independent Advisory Board, concluding that their American logging could have a positive impact on biodiversity.

Drax burned 12.8 million tons of wood in the UK in 2019, and have now announced they are expanding into Asia. After reading about this industrial-scale wood burning, you turn the corner to see a ‘mechanical tree’, created by Klaus Lackner. Robot trees would require power and not help biodiversity, but presumably they would compete less with economic interests than their biological counterparts.

CCU later

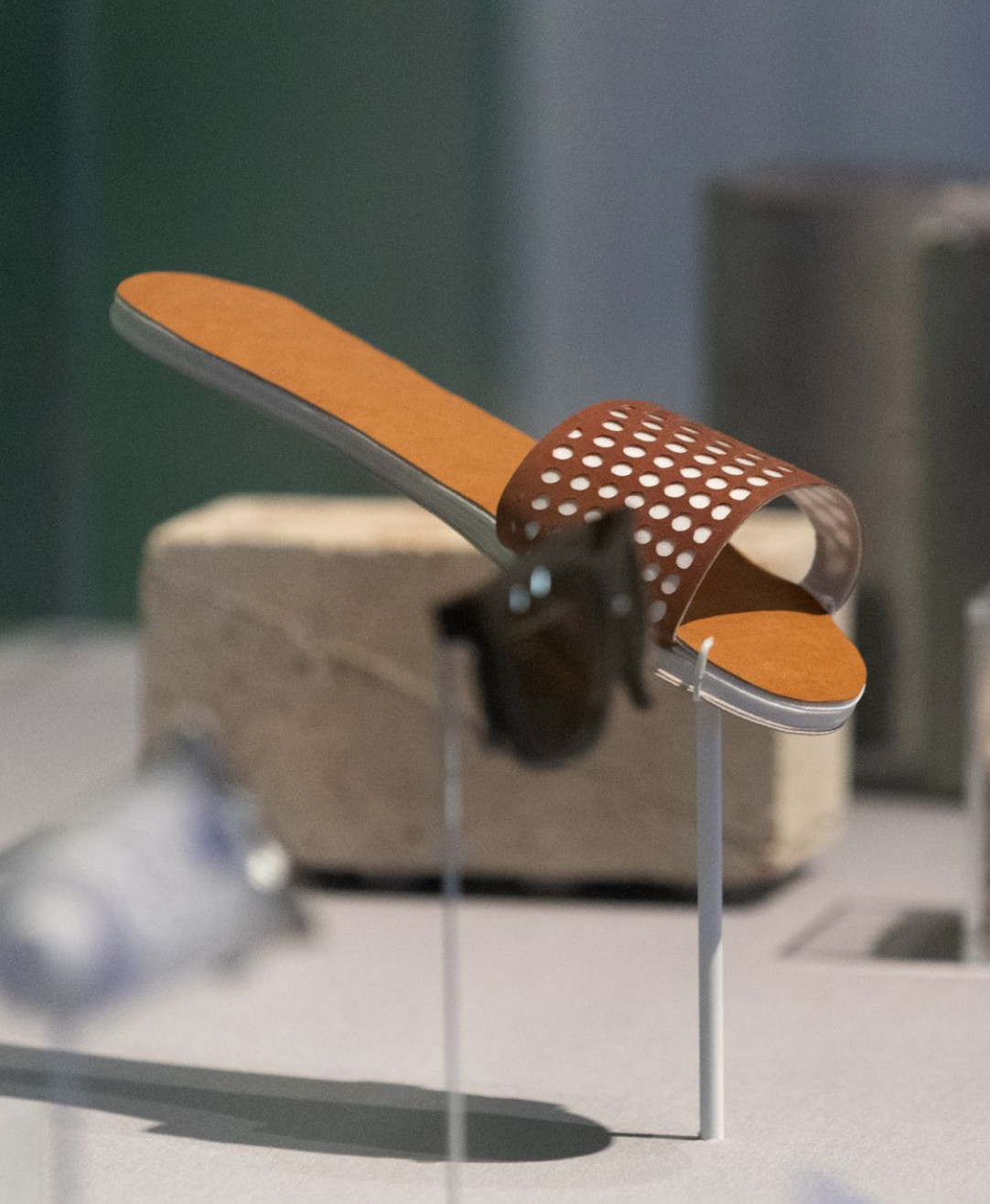

After a brief section on direct air capture and carbon mineralisation, the tour concludes with an array of energy-intensive products made with captured carbon dioxide: sandals, pens, bracelets, even a bottle of vodka.

By my calculations, the average American would have to cough up nearly $9000 to buy 109 bottles of Air Company vodka just to offset their own carbon footprint for a single day¹. Even the Energy Transitions Commission – a coalition of business leaders that includes Drax Power’s CEO Will Gardiner –have recently concluded that storing CO2 in products “does not achieve zero emissions”. That did not stop The Science Museum from presenting such false solutions without criticism or debate.

We need innovation, but educational institutions like The Science Museum should teach about what we don’t know as well as what entrepreneurs claim we do. Hope and optimism are important, but overindulging ourselves on positivity leads to ignoring key questions, such as ‘what if carbon capture technology is never successfully deployed at scale or much of it fails?’ Considering 78% of large scale CCUS projects have failed, it is a question worth asking.

In climate models such as those used by the IPCC, there is only one alternative to negative emissions technologies: degrowth and demand reduction. Shell should know this; they have been running climate models for longer than the IPCC has existed. We need to make less stuff, buy less stuff, and use less energy.

But if you work for a company like C4X Technologies, which captures carbon dioxide and then converts it into ethylene glycol and methanol at 180℃ using nano-catalysts just to make a pair of sandals, energy reduction and degrowth probably are not a cornerstone of your ideology. This was the real problem with Our Future Planet: why are gimmicky companies being given so much influence, rather than academics with more balanced and accurate perspectives?

Exhibition adviser Bob Ward defended Shell’s sponsorship after it was understandably criticised by climate activists, saying that the oil and gas giant “was not involved in the exhibition’s content and design”. This may well be true, but ultimately, it is almost irrelevant if the content and design remains corporate and misleading. It might take more time and money to fully rely on impartial experts for the exhibition design, but greenwashing or not, companies will always have a conflict-of-interest teaching science about the products they are selling.

Endnotes

[1] Unlike other products on their website, Air Company do not state how much captured carbon dioxide is in each 750ml bottle, but in an interview with GQ, the company claimed that every kilogram of vodka removes half a kilogram of CO2 from the atmosphere. A litre of 40% vodka on average weighs 914 grams, and the per capita carbon footprint in the USA is 13.68 tonnes of CO2-e/year, so approx. 37.5kgCO2-e/day. 750 ml of vodka would on average weigh 685.5g, meaning 342.75g of carbon removal. (37500/342.75) x $79.99 = $8752, rounded.

Bertie Harrison-Broninski is an Assistant Editor at ELCI, and a researcher studying bioenergy and BECCS policy for Culmer Raphael. He is also a freelance investigative journalist, with recent work including Al Jazeera’s Degrees of Abuse series and John Sweeney’s book on Ghislaine Maxwell. Find him on Twitter @bertrandhb.