“Time” is the most frequently used noun in the English language. Perhaps that’s unsurprising. From the earliest monastic clockmakers, using time to structure their ‘liturgy of the hours’, to the display on every mobile phone and the practice of giving watches as gifts to mark important birthdays, we are never out of time. The clock gives our experiences communicable form, divides time into portions that make sense on a human scale: seconds, minutes, hours, years etc. But by homogenising time, we level it. Moments of real transformation cannot be conceptualised by the revolutions of minute and hour hands. It is hard to understand that we’re living in an ‘era’ until it passes. There’s a reason that Auden’s ‘Stop All the Clocks’ remains one of the best-loved funeral poems in Britain.

The impact of climate change on the life-support systems of the planet could be described as a slow revolution. But – crucially – it is one which reverses the ordinary Western conception of Progress – in which Western states experience the future first. Now, it is the poorest countries which are described as the frontline of the climate crisis. This provides a starting point for Mark Bould’s new book, Anthropocene Unconscious, centred as it is, around an engagement with Amitav Ghosh’s popular 2016 book, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, in which Ghosh points out that “the Anthropocene has reversed the temporal order of modernity: those at the margins are now the first to experience the future that awaits us all.” The temporality of climate change is not linear. It does not progress along the lines of the economic and political models around which global economies and societies are seen to function.

Bould looks beyond the challenges climate breakdown poses to Western conceptions of Progress, also taking aim at its cultural forms and products – in particular, the novel. According to Bould, “the novel tends to be centripetal rather than centrifugal. To tighten its focus, narrow its range – and miss out the world”. Climate change, to Bould, is always on the peripheries of art, even if we can’t confront it face-on, even if we would like to forget it, even when we think we were safe – such as within that icon of “petro-culture”, the Fast and Furious films. The experience of reading this book is one of being on safari in a temperamental Jeep prone to loud bangs, touted enthusiastically by your lively tour guide, Mark Bould, Reader in Film and Literature at UWE Bristol. It rattles through the Sharknado franchise, zombie films, a handful of contemporary novelists whose work is labelled “good” but their lack of preoccupation with the climate crisis “bad”, aquatic science fiction, arthouse cinema, and more.

While the idea that art has a responsibility not to “miss out the world” but to directly address sociopolitical concerns may sound too earnest for some, this is of course the point. Bould’s issue with the bourgeois novel is that it focuses on a “distinctive and finite social and physical setting”. By doing this, the novel excludes our most pressing reality, that of climate disaster. He dismisses Moby Dick, Middlemarch, and War and Peace as exceptions which are “really just articulations of the norm, that is, of the general tendency of the mundane novel, especially and increasingly in the twentieth century, to focus on the particular and the individual” and he passes over other examples which may undermine his argument.

But Bould makes a fair point. There is a cognitive dissonance in our understanding of the climate crisis. But the inability to confront climate change head on is not confined to art, it is at the heart of the political debate at all levels. Climate change is there but not there. Carbon dioxide is not something we can see, it is not something we can hear, or smell, or touch. Nor can we easily attribute its direct effects. Loss and damage from climate change was one of the most hotly contested issues at COP26.

Is our inability to fit ‘the facts of climate change’ to our common structuring of time partly to blame, and part of the reason why the novel – with some credit as an artform that partly ‘invented’ the individual – is not able to grasp the catastrophe of planetary change either?

Fellows at the University of Antwerp have been researching the problems with a linear conception of time in relation to climate change. Dr Vijay Kolinjivadi spoke to me about their research. “In today’s news, for example, you can hear some titbit related to a four-year electoral cycle, and next you’ll hear that after thousands of years of melting, the Larsen B ice sheet has collapsed. You see these items congealed on the news, and this temporal dissonance means that nothing is shocking.” Climate change eludes us in our current conception of time, and it is a problem in the news, and in global policy debates as much as it is in books.

Climate change is transformation. And it is happening all the time. At the COP26 summit, for example, the UK prime minister Boris Johnson said that “Humanity has long since run down the clock on climate change. It’s one minute to midnight on that doomsday clock and we need to act now.” The problem here is clear. By visualising climate disaster as a state we are yet to arrive at, not only does he erase the 150,000 annual climate change-related deaths which have already happened, not only does he obscure the 20 million stateless climate refugees worldwide, he delineates climate disaster as something that has already been scheduled. We know that this is a dangerous misconception. There are tipping points, like the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, which are unknowable; and we fear that they may even have already happened. The UN process arbiters years by which climate goals must be reached. But the temporalities of the UN process are very different to the temporality of real climate crisis.

If we think back to the news at 10 of March 2020, something was shocking enough to suspend the temporalities of our economic and political systems and bring the world ‘temporarily’ to a stop. Our temporalities shifted to accommodate the COVID-19 pandemic: ten-day self-isolations became common disruptions to our work schedules, journeys were made on foot rather than public transport, in the UK, Christmas was cancelled. The long-drawn-out COP process contrast the speed of the global community’s initial response to the virus. But the COVID response goes to show how quickly nations can respond to a crisis before it becomes a politically polarized issue. The problem with climate change is that the political structure of the electoral system amplifies the effect of climate denial. It becomes too easy to kick climate action into the long grass, and long-term targets divert politicians from the presence of the climate emergency.

Perhaps the unsuitability of the UN process is the reason that child voices have long been so prominent to the climate debate. Before we had Greta Thunberg, we had Severn Cullis-Suzuki, who addressed the 1992 Rio Earth Summit at the age of 12. “Losing my future is not like losing an election or a few points on the stock market – I am here to speak on behalf of generations to come.” She told delegates. Child voices have been able to cut through the climate debate because they are outside the political and economic timeframes which impede progress, and for them, the political long grass is their very real future.

Climate action goes against the temporal grain of both our political and economic systems. For example, research on policymakers developing market-based strategies for carbon-pricing showed that policymakers were “focused on incremental improvement in the design of market mechanisms in order to make them work for politics, rather than on how to rework either market mechanisms or political processes in order to make them work for climate change. In other words, policymakers shied away from climate action which entailed a serious overhaul of the global economy.

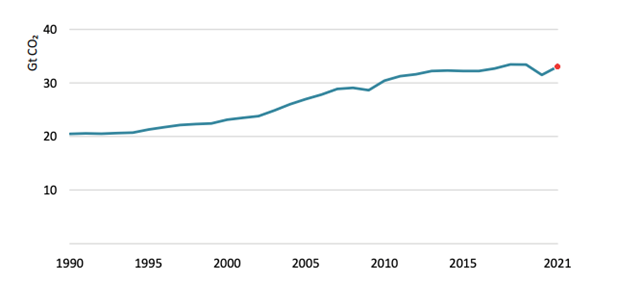

By situating climate goals in clock time, we deal with the climate crisis the wrong way round: we measure success in climate action by when it is achieved, rather than by what is actually achieved as soon as possible. With climate goals pegged around an arbitrary date, real action can be endlessly deferred – and the original dates forgotten. One of the main commitments at the Rio Earth summit of 1992 was to reduce GHGs to the 1990 level by 2000. This graph shows how little this deadline achieved. In 2009, the Copenhagen COP agreed to $100 billion a year of climate finance by 2020. This target is still to be met – and still being haggled over – twelve years later.

So if arbitrary climate policy deadlines are distracting us from real climate action, what’s the alternative? There are other units than clock, or calendar time in which to measure our response to climate change.

Time could be measured by any number of units associated with climate action. Dr Kolinjivadi suggests, for example, that we measure the passing of time in the units of fossil infrastructure which are removed and replaced with clean energy components, or the amount of carbon reductions in the atmosphere. In this iteration, climate deadlines could not, as with GHG emissions targets, simply be sidestepped or extended. “If time is understood as change… then that’s really what should matter when we’re trying to assess whether we’re making progress with climate goals.” Kolinjivadi thinks. Calibrating our understanding of time to the changes in our ecosystem would also allow us to understand what we really mean by climate crisis, and that in some cases, there is no going back.

Mark Bould levies criticism at the novel form for its preoccupation with the individual, arguing that the form has a tendency to narrow its focus, to miss out a world being irreparably demolished by climate change. In some ways, the annual COP processes and the deadlines decided there have been writing the story of the climate crisis. Timelines of climate change found on Wikipedia, or in textbooks, will list events as they have been discussed at the conferences. But by imposing the human social system of time on the climate discussion, we can’t really get a sense of the rate of ecological change and transformation which is taking place. This stops us from acting proportionately to the severity of the crises we face. Amitav Ghosh, Bould’s central critic said, “To imagine other forms of human existence is exactly the challenge that is posed by the climate crisis: for if there is any one thing that global warming has made perfectly clear it is that to think about the world only as it is amounts to a formula for collective suicide. We need, rather, to envision what might be.” Time would be a good place to start.

Endnotes

The Anthropocene Unconscious: Climate Catastrophe Culture is out now from Verso Books.

Lauren is an Assistant Editor at LCR. Her work has focused on geopolitics & climate policy, emissions solutions in the buildings sector, and reviews of new environment titles. Find her LinkedIn here, or email her at lauren@elc-insight.org

Listen to the podcast with Mark Bould:

- Podcast