Learning to both comprehend and feel the environmental crisis is vital to effective climate communication – especially if we have erected emotional barriers to it.

This was the mission of Earthsong, a mix of live and filmed eco-poetry at COP26, the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow. The project was a collaboration between Poets for the Planet, a community of writers and performers working to highlight climate and ecological emergency, and Imperial College London.

Watch Earthsong at COP26:

Inspired by conversations between poets and scientists from Imperial’s Grantham Institute, the event also aimed to straddle the rift between science and the humanities identified by British scientist and novelist C. P. Snow in his 1959 Rede Lecture, Two Cultures.

A good poet can engage our rational and emotional selves simultaneously, bridging the gap between feeling and understanding. One way of doing this is by juxtaposing ideas and images of different emotional shade and weight. In his poem ‘COP26’, for example, Jérôme Pinel contrasts the doleful rat hole with the seed, winged for escape:

“Même au souffle gris d’un trous à rats

La graine ouvre ses … ailes”

“Even in the grey breath of a rat hole

The seed opens its wings”

Or in lines from Pieta Poeta’s poem ‘Vidas Secas’ (‘Arid Lives’), we find the exploited and neglected Brazilian people gilded by legal rights:

“tudo filho de escravo … que só tem na mão a lei áurea”

“the sons and daughters of slaves … who only have the golden law in their hands”

The need for cross-disciplinary collaboration in communicating the environmental crisis is connected to the bridging of feeling and knowledge. Santiago Acosta’s poem ‘Gaviotas’ (‘Seagulls’) about the invasion of a coastal town by seagulls reads like a factual account designed to engage the rational mind. But two thirds of the way through it takes a surreal turn to shake us from a pragmatic understanding of events into a more felt response:

“El veloz pico mordiéndonos una y otra vez. La carne desgarrándose, haciéndose de arena.”

“The swift beak biting us again and again. The flesh being ripped apart, becoming sand.”

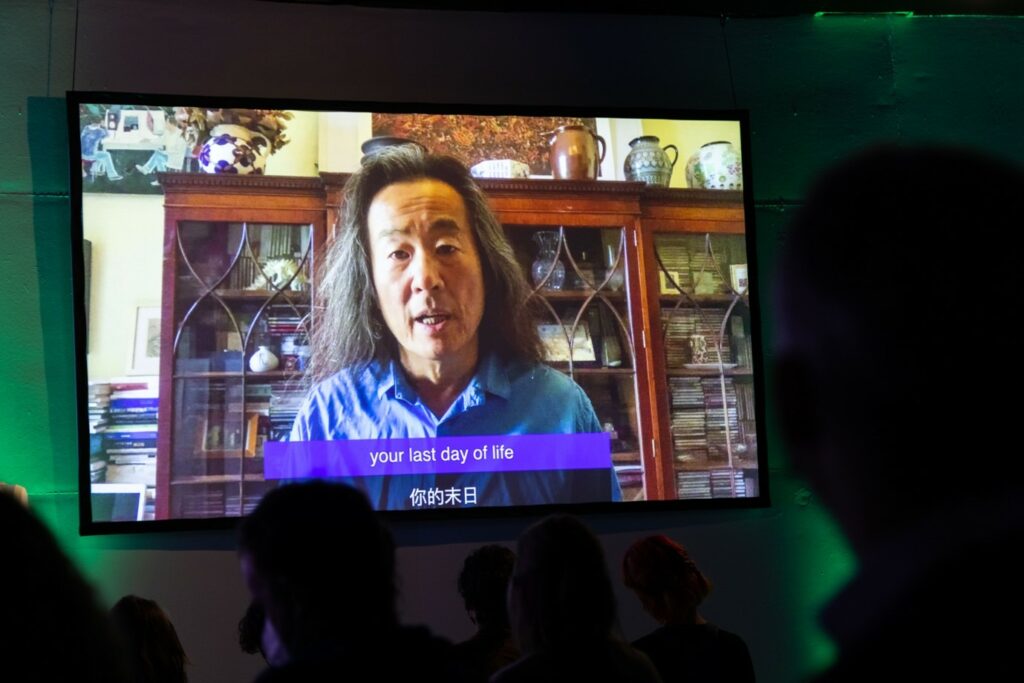

Poetry’s capacity to communicate with our emotional selves becomes even more important if the philosopher David Hume was right, and reason is the slave of the passions. Musical and visceral sonic effects like rhyme, assonance and alliteration, and unexpected juxtapositions of language can inform and rouse our feelings even when we don’t understand, at a rational level, what’s being said. So, when we hear Yang Lian’s line “手按嗡嗡的钟声” (“a hand pushes the bells’ droning hum”), the ringing sound of the words resonates with our emotions even without knowing Mandarin. This stirring of the feelings is deeply necessary if we are to emerge from the apathy and indifference that impedes meaningful action on climate change, pollution and the sixth mass extinction.

Artists in general have a key role to play in communicating the environmental crisis to the public, as they are communications specialists. Every piece of art is a piece of communication, after all, in which the artist tries to express their thoughts and feelings to others in novel and memorable ways. Beyond this, today’s artists are often their own curators, marketing team, social media managers, web designers, application writers, archivists, and photographers, thus equipping them with a wide range of sophisticated communication skills.

If artists are to be mobilised effectively however, their roles need to be budgeted for. While Arts Council England says it is “committed to making sure those who work in arts and culture are properly and fairly paid”, this message did not seem to have reached the organisers of COP26.

Of the close to £100 million reportedly spent by the UK government on hosting COP26, no money was paid to producers of events in the COP26 Green Zone where exhibitions, cultural performances, workshops and talks were held. Performers were not paid by the government for their work or expenses. The sole dispensation, as laid out to producers in the Green Zone Participant Handbook, was that we would not be charged for event room space or exhibition stands.

Tickets to Green Zone events were free, and producers were only notified by the COP26 Cabinet Office team that applications to host events at the conference had been successful in mid-August, which left very little time to apply for funding or sponsorship.

In acknowledgement of the global threat posed by climate change, our Earthsong poets had been drawn from five continents and would perform in twelve different languages. They provided Poets for the Planet with an original poem, an English translation of the poem where necessary, and a film of themselves performing the poem. We subtitled the films to ensure they were as accessible as possible, which involved placing original language and translation on different-coloured bars for clear differentiation and synchronising the texts with the audio.

Though we hoped to offer as many live poetry performances as possible, we knew physical attendance would be limited by travel costs. For those poets who could offer a live performance, the films they created would still be an excellent promotional tool for the conference and for awareness of the climate crisis generally, as clips could be dropped on our social media channels in the run up to, during, and after the conference. We also planned to run a social media campaign in which our friends and followers posted films of themselves performing ecopoems with a COP26-related hashtag, but the late approval of our COP26 application, uncertainties about the Green Zone branding which we could apply to our digital content, and time constraints imposed by our day jobs limited our promotional activities.

On the day of our event, Earthsong ran quite smoothly and was well received by a thoughtful and attentive audience who, during the Q&As, commended the poems and show as ‘stunning’ and ‘astonishing’. Audience questions covered issues of literary influence and translation and focused in particular on the role of poetry in communicating the climate crisis. This focus was very welcome as the problem of how we motivate individuals to change systems and lifestyles in order to bring about planet-saving change was, I felt, insufficiently addressed at COP26.

Poets for the Planet had a lucky funding break – Robin Lamboll managed to procure some seed funding from Imperial College by arranging for Earthsong also to feature at the Great Exhibition Road Festival in South Kensington. This meant we could pay our poets for the work they created and offer a payment towards travel costs. Without this financial support, our Earthsong would not have been heard at COP26.

We would like to see proper funding made available to ensure that the unique ability of artists to engage people both politically and emotionally is harnessed to environmental aims. After all – as Shelley is famously quoted saying – “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”.

You can watch Earthsong on the official COP26 website.

You can find out more about Poets for the Planet here, or you can follow them on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube @poetsfortheplanet, and on Twitter @poets4theplanet.

Ian McLachlan is a London-based writer and performer, and a founding member of Poets for the Planet. He has had more than 50 poems published in magazines and anthologies. His poetry pamphlet Confronting the Danger of Art (Sidekick Books) was displayed in the Treasures Gallery at The British Library as part of an exhibition to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Michael Marks Awards for Poetry Pamphlets. Find him online @ianjmclachlan.

Read more:

- Culture