- Buy here from St. Martin’s Press (314.99 USD)

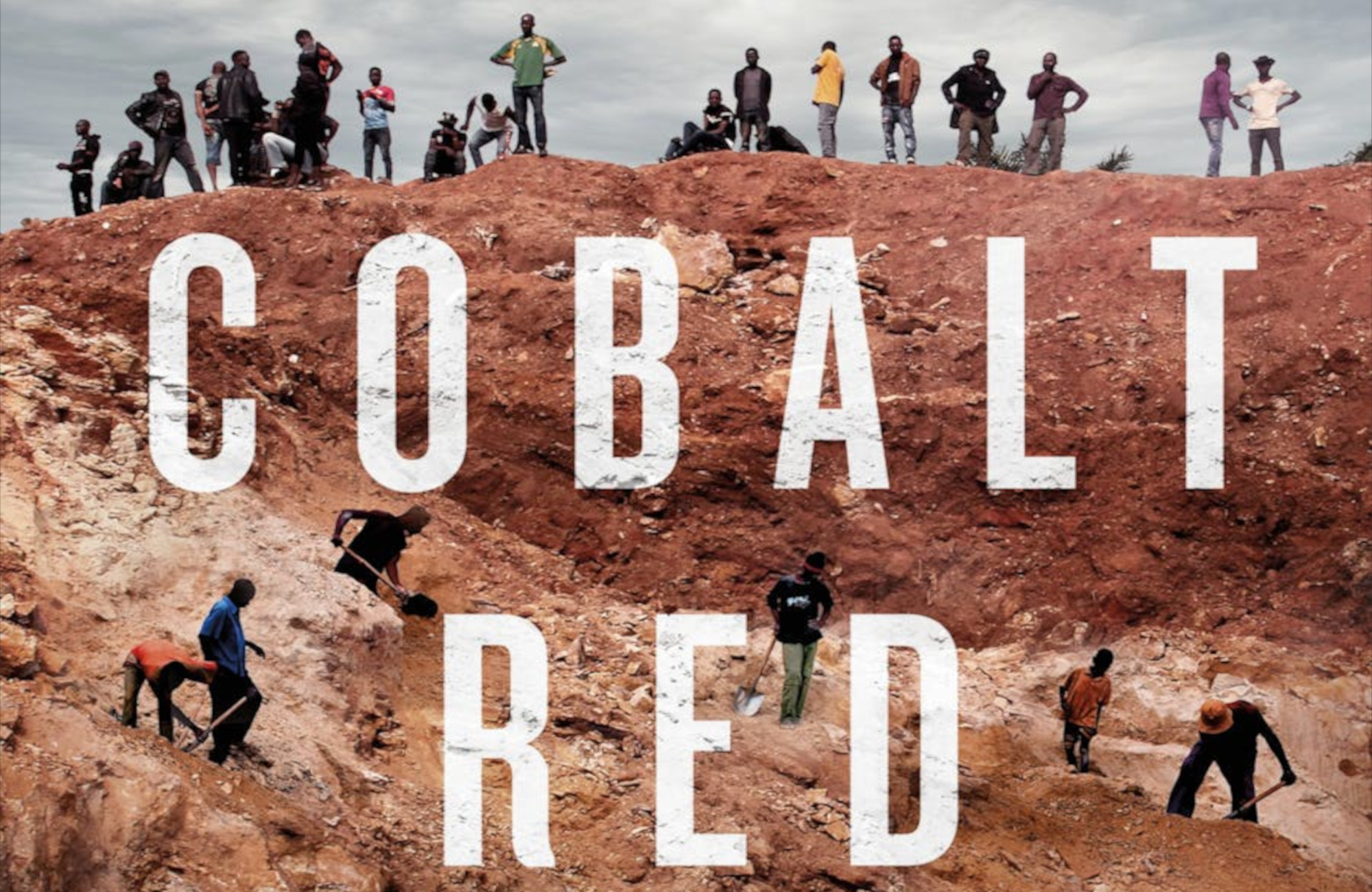

On one side of the world, there are $1,000 iPhones. On the other, there was Elodie in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a 15-year-old paid around 50 cents a day for sexual exploitation. At the age of 15, she was in the late stages of HIV and did not see her sixteenth birthday. At the age of 15, she had a two-month-old son. The thing she had in common with an iPhone was the cobalt trade.

Cobalt is the commodity of the 2020s. If innovation in steel production fuelled the Industrial Revolution, cobalt has a similar sway over the electrical revolution. It is used in almost every smartphone, tablet, laptop, and electric vehicle. There is currently no material like cobalt to produce long-life, durable batteries. The DRC has the largest cobalt reserves in the world, contributing to nearly half of global reserves. 72% of the world’s cobalt is mined there.

ESG standards have given rise to a hearty discussion on the differences between artisanal and industrial-scale cobalt mining. Artisanal miners use little machinery, often working by hand, often in areas with no health and safety regulation. There are 19 major industrial copper cobalt mines in the DRC, where large machinery is used to excavate huge areas of ground, overseen by national or private companies. And of the 19 industrial-scale mines, 15 are Chinese-owned.

For companies looking to buy, industrial cobalt is ‘good’ and artisanal cobalt is ‘very bad’. In 2017, Apple dutifully announced that it would not buy cobalt from artisanal mines. A number of tech companies followed suit. Officially, 30% of the DRC’s cobalt is artisanally mined, but the real proportion could be much higher. In Cobalt Red, Siddharta Kara makes the case that the distinction between artisanal and industrial-scale mining, which allows tech giants to make statements about sustainability and their support of human rights, is a farce.

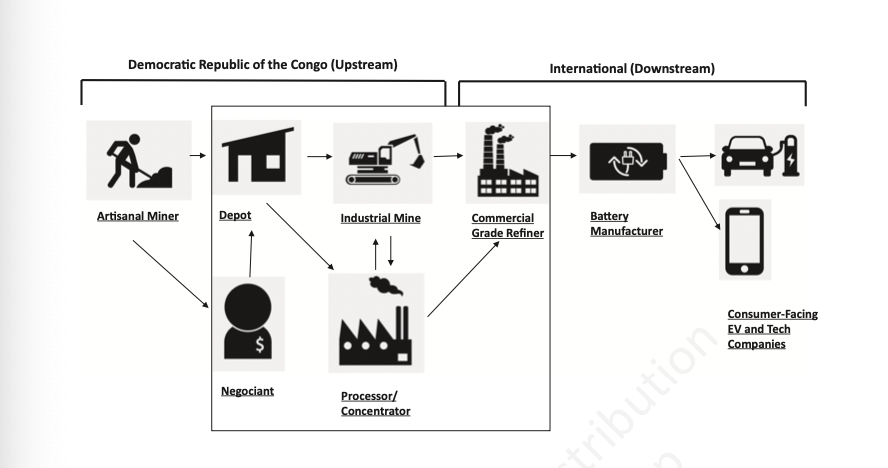

Kara travels round the DRC’s mining districts, and finds a supply chain mired in corruption, where it is impossible to isolate artisanal cobalt from industrial production. This obfuscation can be briefly explained by the following diagram:

Whilst industrially-mined cobalt is immediately delivered to the refining and processing stage, artisanally-mined cobalt is transferred from miner to wholesaler, to depot, and then only after that is delivered to the next stage. Kara argues that the intermediary agents are unnecessary, and only work to enrich external parties at the expense of the miners who put themselves at risk. In this instance, the PR imperative for product manufacturers to disassociate themselves from child labour generates complex, shady supply chains which further disempower the miners.

In Paul Collier’s brilliant 2014 book The Bottom Billion, the four “traps” keeping populations in the poorest countries cycles of poverty are analysed. Collier finds that countries with rich natural resources are time and again impoverished, have reduced human rights outcomes, and are more susceptible to authoritarianism and conflict. Sadly, the DRC supports Collier’s updated concept of a ‘resource curse’.

It is all happening at once: Congolese government officials, centuries of colonisation, and foreign mining companies are all actors in the oppression of Congolese mining districts. As some see it, colonising Europeans have simply been swapped for colonisers from China. But the DRC’s own political instability and lack of centralisation (the last census was in 1984) serve to hide the human rights abuses on which the cobalt trade there is founded.

Artisanally-mined cobalt is, unfortunately, an essential part of the supply chain while long term batteries still rely on that material, as it is higher grade than industrial mined products. Crucially, artisanal miners are not paid fixed salaries. In a day, an artisanal miner can dig up 1-2 sacks of cobalt. The price a wholesaler or depot will pay for those sacks varies between $0.80-2 for a sack that can take 12 hours to fill. Parents who only earn a dollar a day often feel forced to send their children to work as well. Not only are the children exposed to life-threatening working conditions, but they miss out on an education, further depriving them of opportunity to free themselves from the same poverty cycle that ground down their ancestors.

Artisanal miners dig by hand or with light, often ineffectual tools. They often work in sites without safety regulations, safety equipment or masks to prevent mined dust from entering their lungs. Even when children living in artisanal mining areas are not sent to work, indirect exposure to heavy metals from their parents is a severe health hazard. For those working in the mines, inhalation of cobalt dust causes ‘hard metal lung disease’ which can be fatal. Breast, kidney, and lung cancers can all be linked to conditions in artisanal mines, along with an inestimable number of other health problems. Most villages and artisanal mining communities Kara visits do not have basic medical clinics available to them to treat a common cold, let alone cancer. Cobalt Red is littered with stories of miners maimed at work, crippled and slowly dying without any hope of affording crutches, while the prospect of an operation remains non-existent.

Many contracts with foreign countries come with promises to help fund the improvement of the local area’s infrastructure, building roads, schools, and hospitals. For example, in 2008, Chinese-owned SICOMINES signed an infrastructure-for-minerals deal with the Congolese government, promising to pave 6,600 kilometres of road and to build two hospitals and two universities in Katanga, in exchange for mining rights to two concessions near Kolweze: Dikuluwe and Mashamba West. The deal is currently being re-negotiated as these projects have not been executed successfully.

As a European, iPhone-owning, laptop-using, electric car supporting employee in an environment where over-caffeination presents the most significant health hazard, Cobalt Red is a hard read. My naive response was, “Who is sorting this out?”

Supposedly, and certainly from the point of view of the tech industry, that responsibility lies with foreign-backed ESG certification schemes: Responsible Minerals Initiative, the Global Battery Alliance, and in this specific instance, the Cobalt Institute. I spoke to a representative from the Cobalt Institute who assured me that mining companies in the Congo offered “education and training opportunities for the population, community development, and investments in infrastructure development.”

She then said, “imagine: what is normal for us here in terms of education is considered, like, a big deal down there.” This representative worked for an organisation that claimed to be managing the human rights considerations of the cobalt trade. The attitude that the Congolese people have been oppressed for so long that they should be expected to accept lower living standards was disturbing.

But Kara’s travels suggest this is normal. One of his interviewees, a miner, offers this chilling testimony about multilateral regulatory organisations:

“They tell the international community about their programmes in Congo and how the cobalt is clean, and this allows their constituents to say everything is okay. Actually, this makes the situation worse because the companies will say - 'The Global Battery Alliance assures us the situation is good. The Responsible Minerals Initiative says the cobalt is clean.' Because of this, no one tries to improve the conditions.”

Attempts to tackle the human rights abuses associated with the mining industry are consistent only in their ineffectiveness. Kara visits a ‘model mining’ site owned by a Dubai-based mining company, CHEMAF, in partnership with a U.S. based NGO, Pact. Pact’s tagline on its home page reads “An international development organisation at work in nearly 40 countries, Pact builds solutions for human development that are evidence-based, data-driven and owned by the communities we serve.”

When Kara met with a few members of the DRC’s Pact team, they asked to remain anonymous as they “were not supposed to speak with outsiders about the Mutoshi site.” The project had received several million dollars by Apple, Microsoft, Google, Dell, and a commodity trading company called Trafigura to set up a model site. The site provided clean, guilt-free cobalt to CHEMAF’s customers who, among others, happen to be Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Dell. Trafigura is the CHEMAF model site’s primary corporate partner. When Kara visits the site, workers say that Pact staff were only present on site initially, advising on accounting and financial management, and had not subsequently visited.

The CHEMAF model site’s primary aims were the exclusion of child labour from the supply chain and the protection of workers’ health and safety. CHEMAF cobalt is tagged and sent to Trafigura. The site is surrounded by a spaghetti wire fence to keep underage, under-registered workers from entering the site to mine and sell cobalt to different depots. Kara’s report states that the fence was unelectrified, and holes had been cut into it sufficient to allow a small person inside.

Even at the CHEMAF site, the workers are not paid a fixed salary. A site official said this is because of the fluctuations in the price of cobalt. The site also promised to provide education for all of the workers’ children. But of those 2,000 children, only 219 had enrolled, and there was no data for how many had actually continued to attend. The site closed down a few months after Kara’s visits, and neither CHEMAF nor Pact have opened a replacement.

Cobalt Red is diligently researched in his journey through the DRC’s often military-run artisanal mining districts. This is no dry reportage, it’s storytelling, but can feel a little dated. Passages are frequently connected with phrases like “The truth, as ever, waits to be revealed.” Or “I will take you there, just as I took the journey, down the only road that leads to the truth.”

Accusations of the work’s hallmarks of white-saviourism, “recycling stereotypes of Africa as a hopeless wasteland in need of saving” have been printed elsewhere. The framing of Kara’s narrative certainly centres the author as the brave explorer uncovering the issue for the first time. In fact, research in this area has been ongoing for a number of years in universities in Lubumbashi, Leuven and Ghent.

Whilst cobalt industry has systemic issues, it also provides employment and wages for many in the DRC. So, eliminating cobalt from tech products would not necessarily benefit the country either. It is a complex issue, and it is imperative that the safety of miners is given the utmost consideration. An encounter that would stay with any reader comes from a father whose son was maimed in a tunnel collapse which killed 50 others:

[interviewee]: “Now you understand how people like us work?”

[Kara]: “I believe so.”

[interviewee]: “Tell me.”

[Kara]: “You work in horrible conditions and - “

[Interviewee]: “No! We work in our graves.”

Click here to buy Cobalt Red from St. Martin’s Press.

Lauren Sneade is a freelance writer, specialising in the intersection of the arts & climate change. Email her at laurensneade@gmail.com

Read more:

- Culture