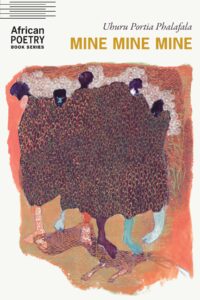

- Buy here from University of Nebraska Press. (17.95 USD)

In times of political and economic uncertainty, investors often buy gold to defend the value of their portfolios. Gold is considered a “safe haven” investment; it will always be valuable. There is a finality to gold’s value; throughout many periods of history, gold has been the very measure of wealth.

But gold does not fall from the proverbial money tree. It is mined – by miners. Mine Mine Mine, Uhuru Portia Phalafala’s epic poem, explores the real price of gold: the lives of Black miners throughout the 20th century. In her scorched poetics of theft and loss, Phalafala indicts America, Dutch slavery, British colonialism and apartheid in South Africa for extracting their “safe haven” assets at the cost of the enslavement and dehumanisation of her ancestors.

My grandfather is dead

He was vomiting blood, my mother says

Lungs contaminated by history

Brimming full with mine dust

In this opening stanza, “history” is not metaphorical. The fatal dust in her grandfather’s lungs was itself the accumulation of decades: a byproduct of his ancestors’ enslavement. The collection is written in six movements, beginning with her grandfather’s migration from the family village, rendering his own children unrecognisable. In Phalafala’s collection, enslavement disfigures familial bonds, a kind of death: “ambiguous loss” precipitates “social death, communal death, familial death.”

The mining industry in South Africa in the 20th century relied heavily on Black migrant labour. Large numbers of Black men, primarily from rural areas and neighbouring countries, were recruited to work in the mines. These workers often lived in single-sex hostels under harsh conditions, enduring long hours and very physically demanding labour. Gold mining is linked to a wide variety of (often lethal) health conditions, and in 2018, an historic class action against the mining industry in South Africa was settled in favour of miners suffering from silicosis, a disease of the lungs caused by dust.

Apartheid was formalised in South Africa in 1948. Under apartheid, Black workers were generally limited to lower-skilled and manual labour within the mining industry and subjected to the Industrial Conciliation Act and the Mines and Works Act, which severely limited their rights to organise. Strikes by Black workers were often deemed illegal. The government and mining companies used intimidation, arrests, and violence to discourage and suppress strikes.

But Black miners still fought for better working conditions, higher wages, and an end to racial discrimination. The strikes that did go ahead were often organised and supported by underground or unrecognised trade unions, such as the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), which operated in secret.

In 1987, the NUM organised a strike at the Anglo-American Corporation’s gold mines in the Witwatersrand region. Thousands of Black miners participated, demanding higher wages and improved working conditions. The strike lasted for several weeks and resulted in clashes with police and mine security forces. While it has been said that the strike served as a catalyst for labour mobilisation in South Africa, the strikers’ aims were not met.

In Mine Mine Mine, the sanctity of the body, love, and family all suffer a perverse inversion for the sake of mining a wealth from which the miners reap no benefit. Phalafala – an English lecturer at Stellenbosch University – creates new poetic compounds to describe her grandfather’s absent relationship as a “stranger-father” to a “stranger-family”. Repeated references to the “city of gold” ring with a tragic irony.

The collection shows that enslavement does not end with the miners. Their wives, and daughters are made implicit. The maternal womb itself becomes a cog working for capitalism, with their “birth canal strengthening GDP”. Death-in-life reappears as a strong motif: stillbirths and miscarriages situate the maternal womb as the origin of suffering, wherein mothers “Deliver sons / into the mine tomb of the state”. Production to feed Western consumerism is juxtaposed with mothers and fathers who are denied the power to raise their own families.

Phalafala’s geopoetics sees her ancestors bound to the land they mine through colonial exploitation which duplicates the same methods in the slave trade as in seizing mines: “Mine mine mine / Ownership paradigm exported / From the auction block.”

The third movement shows that the expansion of US capitalism in response to the Cold War served to dehumanise Black people. The miners become “things”. There’s an element of bodily horror in this analogy as her grandfather’s lungs were literally filled with coal. And under a colonial capitalist system, coal, cotton, sugar, wine, and tobacco were given greater value than her ancestors’ lives.

Swallowing centuries of horror

The coal became our lungs

The cotton became our noose

The sugarcane our diabetes

The grapes our alcoholism

The gold our centuries-old debt

The tobacco our enduring inability to breathe

Phalafala’s verse is highly repetitive, responding to a pain resonating through generations ground down by the same cycles of oppression. Throughout, repeated words, phrases and sounds beat a steady monotony, recalling the hopelessness of liberation from the trauma of cycles of enslavement. “Our state of mind is the state of mines”. Her signature method develops lines through evolving sounds: “breeding, feeding, bleeding”. Her verse is propelled by sound, returning always to exploited, injured bodies, even mimicking the shallow, hyperventilated breathing of miners suffering from silicosis.

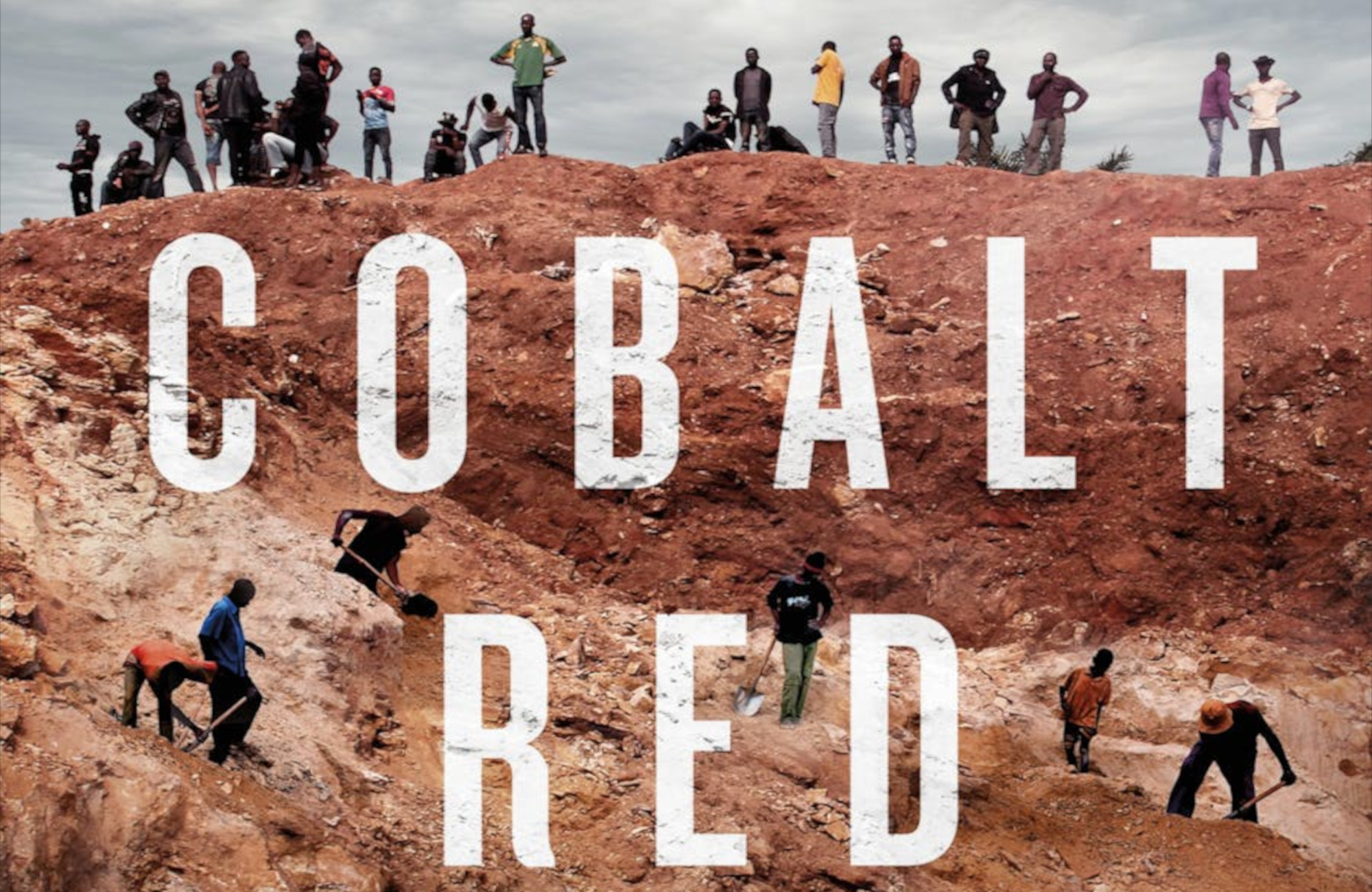

As our collection, The future unrefined, has shown, our need for materials is growing. Extraction of raw materials is often occluded by opaque supply chains, and producers often subscribe to ESG certification schemes which are difficult to verify. While investors may consider gold a “safe haven”, gold mines are anything but. It is vital that extractive industries are held to account, and that historical contexts are remembered and respected.

Click here to buy Mine Mine Mine from University of Nebraska Press.

Lauren Sneade is a freelance writer, specialising in the intersection of the arts & climate change. Email her at laurensneade@gmail.com

Read more:

- Materials