The World Bank’s private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) is trialling a new ‘green equity’ approach, helping its clients in the banking and insurance industries green their finance. This matters, since what the IFC does, others follow.

There is tremendous potential for public funds to be used in a transformative way to shift wider financial flows out of harmful, dirty development towards green, inclusive, and gender-responsive investments. Equity could be a powerful instrument to effect that change.

When an investor takes equity in a company or bank, it gives them a share and sometimes a board seat. So an equity stake can be an important means to influence the future portfolio of a client. Put simply, ‘green equity’ means using equity investments – or shares in a client – to promote environmental sustainability.

The IFC is the standard setter for both the private sector and those who lend to them: the IFC’s Performance Standards are the blueprint for the world’s 32 export credit agencies, for the 126 banks of the Equator Principles, and for other development finance institutions. An estimated $4.5 trillion in investments across emerging markets adhere to the IFC’s Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. On its own account, the IFC is a significant player: its current investment portfolio totals nearly $59 billion, of which over half is invested in financial intermediaries like banks or private equity funds.

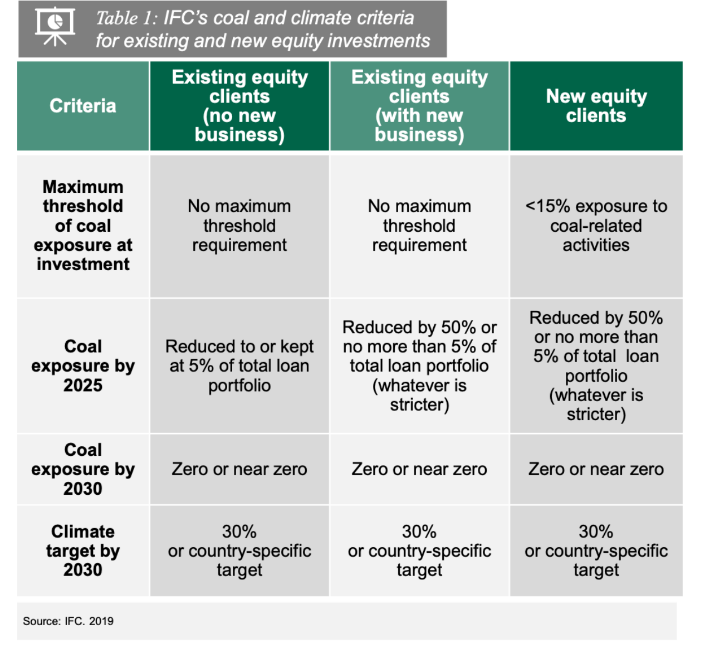

Last year the IFC produced a Green Equity Approach (GEA) that commits the IFC to end equity investments in financial institutions that do not have a plan to phase out investments in coal-related activities. The GEA requires the IFC’s existing and new equity partners to reduce coal exposure to 5% of total portfolio by 2025 and to zero or near zero by 2030.

So, is the GEA working?

Finance watchdog Recourse has been tracking the climate impact of the IFC’s lending for years. In September 2021, Recourse released a report revealing how India’s seventh largest commercial bank – Federal Bank Limited – has turned its back on new coal. The bank received a $126 million equity investment from the IFC in July 2021, which came with GEA strings attached.

The IFC’s project documents describe Federal Bank’s commitment to “terminate financing of development of any new coal-related assets, including coal-fired power plants once the IFC becomes a shareholder in the Bank.” Federal Bank’s own Environmental and Social Management System confirms the step, adding to its exclusion list new thermal coal mines or significant expansion of existing mines, new coal-fired power plants or expansion of existing plants.

Anuradha Munshi of Centre for Financial Accountability in India is one of the authors of the Recourse report, and described Federal Bank’s commitment as “hugely important news, marking a significant change in direction for one of India’s top coal financiers.” She said it “sends a clear message to other banks in India – both state and commercial – that the era of coal is truly over”, and that there are hopes of it causing “a domino effect in India’s financial sector.”

It is a big deal indeed: Federal Bank has extensive exposure to coal. The IFC has provided over $200 million in loans and equity to Federal Bank since 2006, during which period Federal Bank backed coal mine and power plant expansion. Just in the last three years, according to the Global Coal Exit List – a database of coal companies and their financiers – Federal Bank has provided $14 million in loans to JSW Energy, which runs coal plants, imports coal from Indonesia and South Africa, and has shares in coal and lignite mines in India and South Africa. Because of the GEA, Federal Bank is bound to reduce this existing coal-related portfolio to zero by 2030.

Sadly, not all of the IFC’s GEA client engagements have been so successful. As part of a pilot of the new GEA in 2019, the IFC made a $15.36 million equity investment in Hana Bank Indonesia, a subsidiary of South Korean giant KEB Hana. The IFC’s history with KEB Hana goes back over half a century, and in 2007, the IFC helped the bank set up its subsidiary in Indonesia. KEB Hana itself has massive exposure to coal, including through investees Aboitiz, J Power and Arclight, which expose it to over 23,000MW of coal-fired power in the Philippines, Indonesia, Australia, China, Japan and the US. KEB Hana also invests directly in coal projects such as the 1,120MW Mong Duong coal plant in Vietnam, and the 1,070 Loy Yang B and 850MW Milmerran coal plants in Australia.

Following the IFC’s 2019 equity investment, Hana Indonesia itself invested in one of the biggest new coal complexes on the planet, Java 9 and 10. The project will release 10 million tonnes of carbon dioxide each year, which over its lifetime will total 250 million tonnes: the equivalent to the annual emissions of Spain.

Indonesian groups have branded Java 9 and 10 a disaster “in terms of environmental, social and health issues, in an area already covered with coal fired power plants and industries” and have called on the IFC to persuade its client to divest from the coal plants.

The very different outcomes in the cases of Federal Bank and Hana Bank come as no surprise to the NGOs engaged with the IFC on its GEA. These NGOs warned the IFC during consultations that there was a significant GEA loophole: it does not explicitly require clients to rule out new coal investments. In response to a letter from Indonesian NGO, Trend Asia, the IFC wrote, “the GEA does not prevent IFC equity investees from having portfolio exposure to coal, which remains an important part of the energy mix for many of the World Bank Group’s member countries. That exposure may fluctuate up or down in the years ahead… The end goal is to reach zero or near zero by 2030.”

We at Recourse and our partners argue that allowing clients to invest in new coal goes against the spirit and intention of the GEA. While some, like Federal Bank, will interpret it as a signal to stop funding coal plants, others like Hana bank will carry on business as usual. It is unlikely Hana bank will be able to meet the GEA’s requirement that clients reduce coal exposure to zero or near zero by 2030. The term of its 2020 loan to the Java 9 and 10 coal plants runs for 15 years – so to 2035, well beyond the 2030 deadline.

The Green Equity Approach has great promise, but it needs to go further and faster. It will only meet its potential if it is reformed – the IFC did promise a review after a couple of years’ putting into practice. Our report’s recommendations are that the GEA must:

- close its coal loophole, banning any new investment in coal. The Federal Bank example has demonstrated that this is possible.

- reach more clients (at present, the IFC has signed up only 5 of its 68 active equity clients). The IFC should use its influence with its equity partners to encourage them to sign up.

- encourage a shift away from all fossil fuels, not just coal. This would be in line with the World Bank’s existing position of not funding upstream coal and gas.

As a global standard setter for both private sector banks and the public sector financial institutions that invest in them, the IFC has a unique role in ensuring equity transforms our energy future. The GEA has now shown that it can help to stop equity clients from backing dirty coal. With these changes, it would be a powerful tool for green finance.

You can read the full report, ‘Putting people and planet at the heart of green equity’, here.

Kate Geary is Co-Director of Recourse, an NGO which campaigns to redirect international financial flows away from dirty, harmful investments, towards greener and more inclusive develoment. You can send her an email here.

Read more:

- Opinion

- By Hannah Greep

- 23 November, 2021