Sarah Katz-Lavigne is a researcher at the University of Antwerp, studying mineral supply chains linked to the “green energy” boom, particularly cobalt mined in southeastern Democratic Republic of Congo. She was interviewed for Land and Climate Review by Lauren Sneade.

You have recently returned from a two month visit to the DRC. Tell us about your trip.

It was a very interesting experience. I visited the Kolwezi region, the area of Lubumbashi, and then I was able to go to eastern Congo, which is quite well known for mining of the three Ts and Gold, as they’re called, or Tin, Tantalum and Tungsten, which are well known as so called ‘conflict minerals’.

I last visited for my PhD in 2017, and right after that, the cobalt boom began. A massive increase in demand, very rapid spikes and drops in pricing, and increased interest from different national actors.

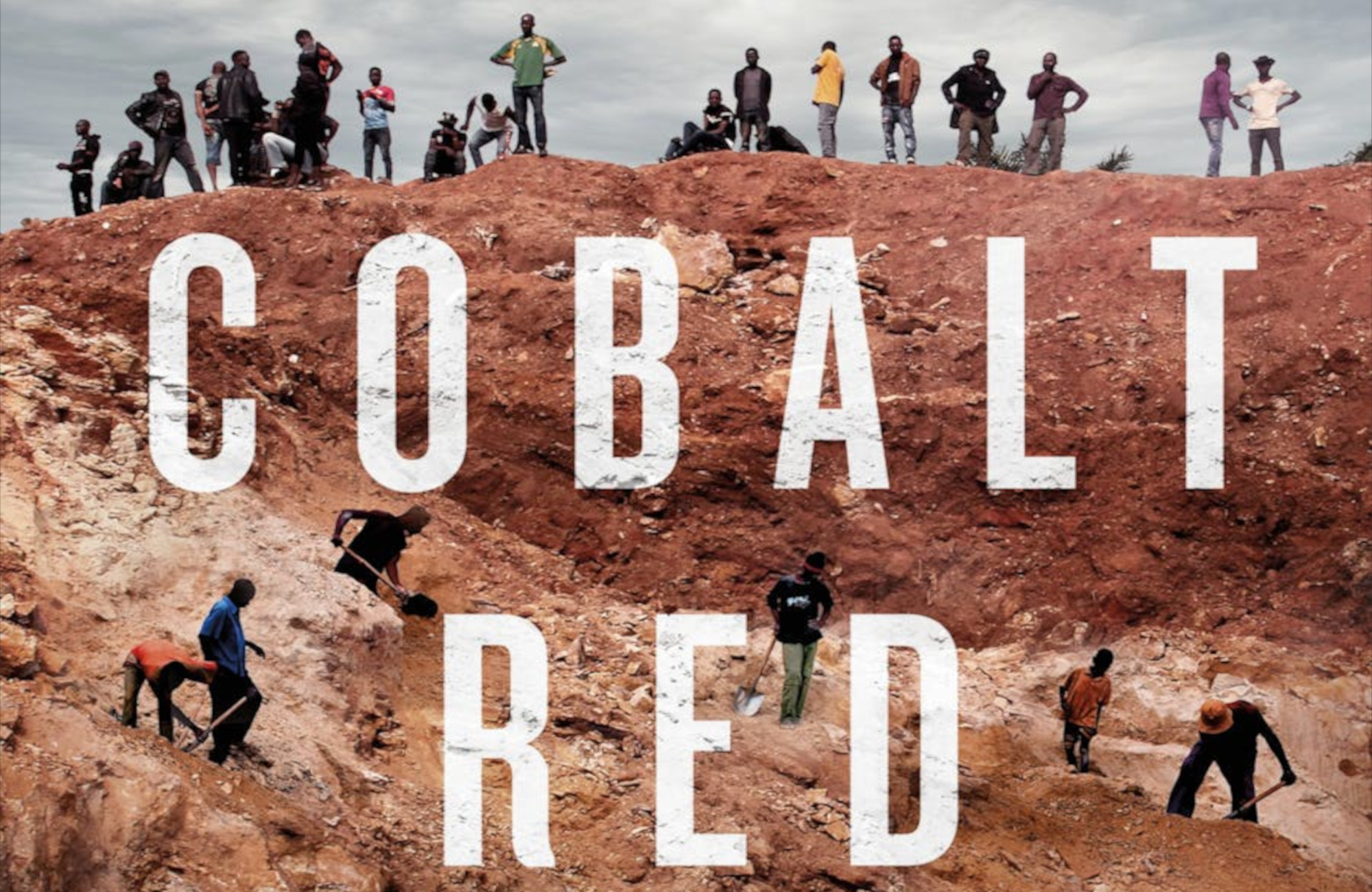

Going to Kolwezi in that context and seeing how quickly it’s developed, how much people say it’s changed in the last several years, and just how much actual mining is going on around and even in the city itself was definitely eye opening for me.

International coverage often suggests artisanal mining, specifically, wreaks devastation on rural communities. Did you see evidence of that?

Yeah. Even in 2017, there was some inkling of that. Amnesty International and a Congolese NGO called AfreWatch (or Africa Resources Watch) really got the ball rolling in this regard. They released a report in 2016 called This is what we die for. It really drew attention to the poor conditions in artisanal mines, the presence of children, and the abuses by security forces. Particularly the issue of mine collapses and poor safety conditions is a very concerning one for people who work in the sector.

These issues are challenging because they are not specific to artisanal mining, but have been very much ascribed to artisanal mining as though that is the sole cause. In reality, the artisanal mining sector, the industrial mining sector and government management of the cobalt and copper sectors are all extremely intertwined. I’m cautious not to contribute to an oversimplification – even demonisation – of the sector, because policymakers in the region themselves are often looking for an excuse to push out artisanal miners and replace them with big companies.

How important is artisanal mining to community economies and histories?

It has a much longer history than just recent decades, but during and since the structural adjustment era, it’s taken on a really massive importance for communities not only in the copper and cobalt mining areas, but also in eastern Congo.

It’s estimated to directly provide livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of people across the country and then millions indirectly when you include people who depend on the income from artisanal miners. And research has shown that compared to industrial mining, it makes a really significant economic contribution at local level.

My own work has shown that oftentimes workers at industrial mining companies live elsewhere, and when they leave a site, they’ll repatriate their earnings. They won’t really spend locally and you don’t see a lot of impact. Artisanal miners very much spend locally, even integrating into the community when they are from other areas. They give a lot of business to women, shopkeepers, people who supply tools, clothing, food and drink and so on.

How significant is the issue of child labour?

It’s difficult to determine how many children are involved. You often hear the figure of 40,000 children working in the mines. Recent research has suggested the figure may actually be far lower, but you tend to get uncritical repetition of these large numbers.

That’s not to say that there aren’t children doing this work. It’s an emotionally visceral and very important issue, because so many Congolese parents do not want their children doing this work.

It is often employment of last resort, and constructive solutions are not being sought. The usual first response is to get children, and often women as well, out of mine sites. But I heard a lot in my travels recently that they’re taken out, temporarily given schooling, but end up returning because they have no longer-term prospects. And so to me that raises questions about the sustainability of these approaches. There is a lack of sensitivity to the realities of parents and women who have no childcare options other than bringing their children to the mine with them.

Nuance is definitely needed to understand the driving forces behind these issues. I’m not sure international scrutiny has actually improved things, or just pushed harm underground. Policymakers really need to consider unintended consequences when they do this kind of messaging focused on one issue with a very emotional appeal.

So what does need to happen?

A lot of the time, the things that do work and have been shown to be more manageable or more effective for improving lives of minors are not politically feasible, which is why they’re not implemented.

What has happened across the board is that artisanal miners have been expelled from the most valuable mining sites because these sites have been allocated to large scale companies by the Congolese government. So the uncertainty around how miners have to operate, even when they’ve been operating in a given area for 20 years (in the case of one cooperative that I saw), is a major impediment to improvement. Artisanal miners are simply tolerated until the next big investor comes along.

The favouring of short term solutions, while also criminalising or illigitimising smaller actors, is very problematic. There needs to be a more sustained way to engage with them, to foster the structures that already exist. And that doesn’t just include the formal cooperatives, which, as many people have shown, are not always the most accountable or representative, and often aren’t integrating women into their operations in a very advantageous way. Informal mechanisms, including how women work together to pursue their livelihoods, also need to be taken into account much more. Otherwise those without the resources and capacity to fulfil legal requirements are overlooked.

Would you say that there are any instances of problems within the sector being tackled correctly? Are there initiatives that are working?

What I’m seeing in the Driving change project that I’m working on is that a lot of these initiatives and responses are led or driven by multistakeholder partnerships, and directly pushed forward by the influential actors. So you have initiatives like Fair Cobalt Alliance, which has several corporate actors engaged, as well as NGO actors and others. But the problem is that these actors tend to see it as an issue of legality and legitimacy.

So to them, any actor that is legally compliant is legitimate, and anyone else needs to stop what they’re doing or be pushed into alternative livelihoods. But as we’ve said, this activity is one of the only viable options for many people to earn a living. Agriculture is much more difficult to pursue, for instance, in large part due to the environmental damage in the region from cobalt mining.

There are some initiatives that look good on paper in terms of having potential to advance the situation, such as the government’s idea of implementing an Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (EGC). This is supposed to become a state buyer for cobalt and therefore give artisanal miners a better purchaser and a better price. Artisanal miners currently have little say in negotiating price, or in even asking for an independent evaluation of the weight or the grade of the mineral, or the percentage value, which is often very heavily disputed and it really depends on the equipment you’re using.

So some of these things look good, but face major implementation challenges. There isn’t political will for the government to be purchasing minerals at a truly fair price, because that wouldn’t be advantageous for the many other actors who are also seeking to continue their access to the supply.

Lauren Sneade is a freelance writer, specialising in the intersection of the arts & climate change. Email her at laurensneade@gmail.com

Read more:

- Materials